Why Hiding Or Changing Facts To Protect Against ‘Panic’ Can Cause One

By Thom Fladung, Hennes Communications

When your leaders say they must downplay the truth of a crisis to protect against mass panic, it may be time to…panic.

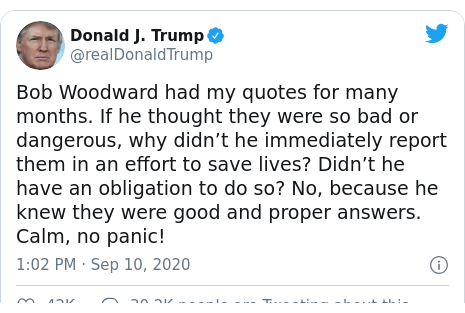

The latest example is playing out relentlessly on news sites and social media. Bob Woodward’s new book “Rage,” cites how President Donald Trump, in taped interviews, told Woodward in February and March of the dire threat posed by the COVID-19 pandemic – and that he would intentionally not level with people about that threat.

Since that news broke and in the face of a torrent of criticism, President Trump has explained his stance: “So the fact is, I’m a cheerleader for this country,” Trump told reporters. “I love our country. And I don’t want people to be frightened. I don’t want to create panic, as you say. And certainly, I’m not going to drive this country or the world into a frenzy. We want to show confidence. We want to show strength.”

Let’s set aside the politics – which may be a pipe dream in these extraordinarily politicized times. In any case, we’re not here to debate the politically correct move. But from a crisis communications standpoint, the playbook is clear and has been proven over and over from numerous crises over time: People don’t panic when given clear, understandable facts about a situation. But people will recoil – and perhaps panic – should they learn later that the threat was downplayed, putting them in more danger.

Peter Sandman, one of the nation’s leading experts on risk and crisis communications, and a friend of Hennes Communications who we’ve often cited, anticipated this in March when he wrote a piece for the Sunday Times of London that he headlines on his blog ”When It Comes To The Pandemic, Scared Is Good.”

What is the best way to communicate about a crisis like a widespread public health issue? In a piece Sandman co-authored with Jody Lanard it’s described as “the Holy Grail of risk communication: to inform and warn the public, and to get the public to respond appropriately to scary new information, without actually scaring people.”

Dr. Michael Osterholm, a noted epidemiologist and director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota, put it another way, for USA Today: “Just tell the truth. What do we know, and what don’t we know. … Don’t minimize issues. My job is not to scare people out of their wits, it’s to scare them into their wits.”

Yet we see that choice to shield rather than inform being made time and again. If you’re helping lead an organization, it’s worth thinking about now – before the crisis. Consider the case studies that Sandman and others present. And think very hard about whether the frightening information you now hold will cause the people you’re responsible for to panic – or prepare.

Thom Fladung is managing partner of Hennes Communications. To learn more about Hennes, go to www.crisiscommunications.com. To reach Fladung, email fladung@crisiscommunications.com or call 216-213-5196.