When Crisis Management is in the Dark: Front Seat at the Atlanta Airport Power Outage

[by Howard Fencl, Hennes Communications]

Atlanta’s sprawling Hartsfield-Jackson Airport (ATL) may boast awards for efficiency, but after electrical switching gear fried and fire took down power – and backup power – for 30,000 souls left stranded in the dark for 11 hours, ATL won’t be winning crisis communications awards any time soon.

I was caught in the middle of the outage with my wife as we were heading home from a weekend holiday visit. Lugging our gear to our gate at the end of the “B” concourse, the lights blinked out for a few seconds, then came back on. Nervous laughter rippled through the concourse, and everyone pressed on. In another minute, the lights cut out and stayed out.

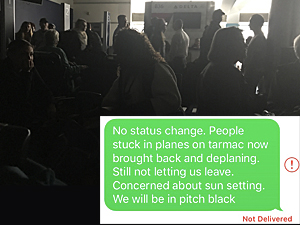

Though it was just after 1 p.m., the concourse was dark. We camped out in seats by the windows at the end of the concourse, reasoning that at least we had some daylight. An hour passed. No announcements. Smart phones randomly lit up the terminal like fireflies with people desperately looking for information – any information. Many people called relatives asking them what they were seeing about the outage on the news. Twitter wasn’t much help at this point.

Another hour passed. No announcements. We could hear a few other travelers saying “…a construction worker cut a cable,” and “…a million people in Atlanta have no power now!” People speculated on other possible causes – was it terrorism? Did Russians hack the electrical grid? The restrooms – at least the men’s – were pitch black. Since the sinks and soap dispensers were motion activated and powered by electricity, they didn’t work. Drinking fountains dried up. Toilets flushed, but for how long? Walking back to the gate, airport vendors staffing sandwich and drink kiosks began extorting the trapped crowd, hawking bottled water for $10 a bottle – cash.

When an airport worker finally made her way up the concourse aisle shouting a talking point or two at the top of her lungs, we didn’t know much more other than “…they’re troubleshooting the problem,” and “…for security reasons, they’re not letting anyone leave the airport.” She delivered this message, then moved ahead a few gates, shouting it again, all the way up the concourse.

If ATL had a crisis communication plan, there was none in evidence during the December 17 blackout. They either had no plan – or they failed to execute their own plan. Operational issues aside (no bullhorns for announcements, no emergency lighting evident), ATL should have immediately begun communicating at regular intervals – even though initial information was meager. The vacuum of information left a gaping maw that people readily backfilled with conjecture and speculation – all of it wrong. What should ATL have done?

- Before the crisis, designate incident communication teams, assigning each team a concourse.

- At the onset of the crisis, direct each team to deliver a few general talking points to its assigned area. (“We don’t know much yet but crews are working on the situation; in the meantime we ask everyone to be patient and keep calm – we’re all in this together.”)

- Announce that you will update everyone every 15 minutes with new information. Stick to this schedule even if available information hasn’t much changed.

- Let people know what to expect. (“…because the power is out, fountains and sinks will not be working…we are working on getting bottled water in here as soon as we can.”).

- Answer as many questions as you can. (“…for security reasons, no one is being allowed to exit the airport. I’ll let you know if that changes.”)

None of this happened during the time we were stuck at ATL. One announcement was it. To add insult to injury, overhead speakers began blaring an automated message (“…Attention! Attention! An emergency incident has been reported!”) punctuated by piercing peals of honking electronic horns and strobing lights. The announcement repeated. And repeated. And repeated. A bad situation quickly became worse as this pointless announcement grated on already-raw nerves.

In the fourth hour I happened to notice another airline worker in the center of the aisle talking to a small group of people and I overheard her saying ATL was now letting people who wanted out, to walk out of the airport. But it was a 20-minute walk culminating in lugging baggage up a steep, motionless escalator. We jumped at the chance. Emergency lighting was on in the long walkway by the halted airport train. Crossing another concourse, the tinny acrid smell of electrical fire surrounded us. We trudged through to the end, where a massive swarm of people squeezed down into three lines to struggle up the escalator stairs. Reaching the top, we learned that MARTA public transit was still running. We packed into a crowded train car and headed north for an unexpected encore visit to family.

We still knew nothing about what had happened. And for the people still stuck at ATL, seven more hours of darkness and uncertainty was still ahead.

Public institutions and all public-facing organizations must have crisis communications plans in place that anticipate the worst, have messages ready to go at a moment’s notice, and have a crisis management team with clear assignments. Importantly, they need to rehearse crisis scenarios to test their plans – and to tweak them where inefficiencies are discovered.

Your business could benefit greatly as well. If you don’t have a crisis plan, put it in your budget for the New Year. If you have a plan in place, have it audited to be sure it’s up to date. Run a crisis drill so you and your crisis management team are a well-oiled communications machine. Ignore all of this at the risk of leaving your most important audiences trapped in the dark.