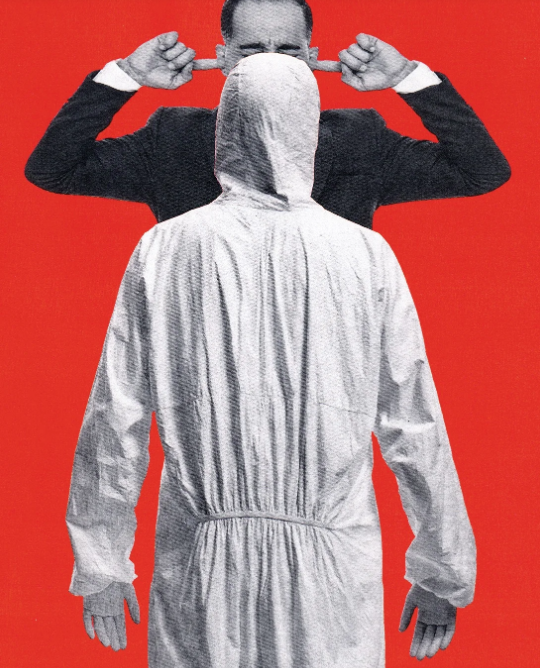

Science vs. Politics

When the H1N1 Swine Flu vaccine became available ten years ago, at first the scientists and other public health experts said that pregnant women should immediately get the vaccine. Then they said it should be administered to those over 65 years of age, then it was anyone who was immunocompromised, with changing death projections and viruses that waxed and waned. It was the same with MERS and SARS.

In actuality, those two organizations, and the doctors and scientists who work in that industry, knew exactly what they were doing. They were in a battle with a virus. And as happens in all battlefields, the terrain, personnel and facts can – and often do – change.

And at every turn in that pre-Facebook age, the mainstream media, and especially the cable-TV pundits pounced on every change, accusing the CDC and WHO of not knowing what they were doing. And as the threats from H1N1, SARS and MERS subsided, I clearly remember telling the audiences at the many crisis management seminars I taught at the time that one day the media would rue the day they did damage to the science of epidemiology in their breathless pursuit of higher ratings.

The one thing H1N1, SARS and MERS had in-common was the fact that the politicians stayed out of the way. Rarely did presidents and governors speak or offer opinions. Instead, they deferred to the experts.

Today, with the insertion of state-sponsored misinformation and manipulation from China, Russia and North Korea mixed with incorrect and more misleading information from the highest levels of government in D.C., decisions about masking, timelines and social distancing have become politicized and weaponized.

Under the best of circumstances, the public is easily confused, especially when they receive mixed and inconsistent messages.

– Bruce Hennes, Hennes Communications

————————————————

In this recent article from The New Yorker, writer Charles Duhigg lays it out for us:

Seattle’s Leaders Let Scientists Take the Lead. New York’s Did Not

The initial coronavirus outbreaks on the East and West Coasts emerged at roughly the same time.

But the danger was communicated very differently.

Epidemiology is a science of possibilities and persuasion, not of certainties or hard proof. “Being approximately right most of the time is better than being precisely right occasionally,” the Scottish epidemiologist John Cowden wrote, in 2010. “You can only be sure when to act in retrospect.” Epidemiologists must persuade people to upend their lives—to forgo travel and socializing, to submit themselves to blood draws and immunization shots—even when there’s scant evidence that they’re directly at risk.

Epidemiologists also must learn how to maintain their persuasiveness even as their advice shifts. The recommendations that public-health professionals make at the beginning of an emergency—there’s no need to wear masks; children can’t become seriously ill—often change as hypotheses are disproved, new experiments occur, and a virus mutates. The C.D.C.’s Field Epidemiology Manual, which devotes an entire chapter to communication during a health emergency, indicates that there should be a lead spokesperson whom the public gets to know—familiarity breeds trust. The spokesperson should have a “Single Overriding Health Communication Objective, or sohco (pronounced sock-O),” which should be repeated at the beginning and the end of any communication with the public. After the opening sohco, the spokesperson should “acknowledge concerns and express understanding of how those affected by the illnesses or injuries are probably feeling.” Such a gesture of empathy establishes common ground with scared and dubious citizens—who, because of their mistrust, can be at the highest risk for transmission. The spokesperson should make special efforts to explain both what is known and what is unknown. Transparency is essential, the field manual says, and officials must “not over-reassure or overpromise.”

The lead spokesperson should be a scientist. Dr. Richard Besser, a former acting C.D.C. director and an E.I.S. alumnus, explained to me, “If you have a politician on the stage, there’s a very real risk that half the nation is going to do the opposite of what they say.” During the H1N1 outbreak of 2009—which caused some twelve thousand American deaths, infections in every state, and seven hundred school closings—Besser and his successor at the C.D.C., Dr. Tom Frieden, gave more than a hundred press briefings. President Barack Obama spoke publicly about the outbreak only a few times, and generally limited himself to telling people to heed scientific experts and promising not to let politics distort the government’s response. “The Bush Administration did a good job of creating the infrastructure so that we can respond,” Obama said at the start of the pandemic, and then echoed the sohco by urging families, “Wash your hands when you shake hands. Cover your mouth when you cough. I know it sounds trivial, but it makes a huge difference.”At no time did Obama recommend particular medical treatments, nor did he forecast specifics about when the pandemic would end.

Whereas the C.D.C. protocol encourages politicians to practice restraint, it invites the lead scientific spokesperson to demonstrate his or her advice ostentatiously, and to be a living example of the importance of, say, wearing a mask or getting a shot. When polio inoculations began, in the nineteen-fifties, many people worried that they were unsafe, so New York City’s commissioner of health—who happened to be married to the E.I.S.’s founder—invited reporters to watch schoolchildren getting injections. She also enlisted Elvis to publicly get his shot.

E.I.S. personnel in the field have carried boxes of masks and gloves to distribute to pilots, flight attendants, journalists, and health workers—supplies that may not be needed by the recipients but emphasize how important universal compliance is. When Besser gave briefings during the H1N1 pandemic, he sometimes started by describing how he had recently soaped up his fingers, or pointedly waited until everyone was away from the microphone before taking the stage. At the time, there was almost no chance that Besser and his colleagues were at immediate risk of contracting H1N1. “To maintain trust, you have to be as honest as possible, and make damn sure that everyone walks the walk,” Besser told me. “If we order people to wear masks, then every C.D.C. official must wear a mask in public. If we order hand washing, then we let the cameras see us washing our hands. We’re trying to do something nearly impossible, which is get people to take an outbreak seriously when, for most Americans, they don’t know anyone who’s sick and, if the plan works, they’ll never meet anyone who’s sick.”

Public-health officials say that American culture poses special challenges. Our freedoms to assemble, to speak our minds, to ignore good advice, and to second-guess authority can facilitate the spread of a virus. “We’re not China—we can’t order people to stay inside,” Besser said. “Democracy is a great thing, but it means, for something like covid-19, we have to persuade people to coöperate if we want to save their lives.”

For the rest, please click here.