Fake News: The Real History – and How to Deal with It Today If You’re a Target

By Thom Fladung/Hennes Communications

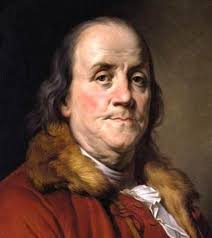

In 1782, Benjamin Franklin, while serving as American ambassador to France, reported a shocking story. American revolutionary soldiers had found bags with more than 700 scalps of soldiers, boy, girls and even infants. The massacre, Franklin wrote, was the work of Indians who were allied with King George. And the Indians had included a note to the English monarch hoping he would “be refreshed” by these presents.

Except Franklin made up the story. As Robert G. Parkinson, an assistant professor at Binghamton University, wrote in the Washington Post, Franklin created a fake issue of a real Boston newspaper, including other made-up stories, and sent the faux papers to colleagues. Whereupon the scalps story made its way into real newspapers in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Connecticut, New York and Rhode Island.

In other words, it was all fake news. Just in case you thought this was a recent phenomenon, practiced by scoundrels, not an ancient art embraced by one of our revered founding fathers.

To be sure, fake news isn’t new. Indeed, it’s another indicator that we’re reliving the “yellow journalism” era of the late 1800s and early 1900s, when printing presses and paper suddenly were cheap, and newspapers were springing up everywhere, leading to intense competition for attention that prompted sensational and even made-up stories. (Sound familiar?)

But it’s little solace that fake news is old news if you’re caught up in a fake news story, with your reputation on the line.

It’s also not going away – in part because fake news can be quite effective in pushing a point of view and in part because our dedication to protect free speech also protects the purveyors of fake news.

“It is extremely difficult to define in a clear way the boundary between fake news and alternative viewpoints,” University of Minnesota law professor William Mceveran told the ABA Journal. “You may know it when you see it, but it is a danger to impose limits on speech.”

The yellow journalism era began to fade when readers increasingly demanded substantive, corroborated reports from their news providers – and when publishers like Adolph Ochs of the New York Times proved that “clean, dignified, trustworthy and impartial” reporting could be both ethical and economically lucrative.

Could that more pleasant history repeat itself? Perhaps. Although these times seem too inflamed for cooler heads to prevail any time soon. In an “Ask History” forum on the Reddit website, the moderator of the conversation wondered “With all the media distortion these days, I’m curious what it was that brought objectivity to newspapers after the last spate of yellow journalism, and if that could work again today.”

That online debate quickly devolved into a vicious, hysterical fight between participants. One of the more mild and few profane-free rejoinders was “you half-wit ditto head.”

Hennes Communications’ principles for effective use of social media include dealing with false and misleading reports. But the first rule we’ll suggest is don’t fall in love with the rules, because they’re changing constantly.

Consider that one of the most infamous episodes of a false report gaining huge traction during last year’s presidential campaign involved a single tweet from a man who posted pictures of buses and said they were evidence of paid protesters being bused to demonstrations against Donald Trump. They weren’t. The buses were for attendees of a nearby software conference.

Nevertheless that post was shared at least 16,000 times on Twitter and 350,000 times on Facebook, as the New York Times’ Sapna Maheshwari outlined in the excellent “How Fake News Goes Viral: A Case Study.”

For people who study reputation management on social media, the twist was this: The original Tweeter had 40 followers. And one of the “rules” has been to avoid adding fuel to the fire by reacting to a critic with few followers. The bus tweet is an extreme example, as it came amid the most hyper-charged national election in memory. It’s also, though, a reminder that the potential damage from a social media post cannot be judged by the initial audience.

Here are some other guidelines:

- Use social media before the crisis. Know where your customers and key stakeholders are on social media and engage them. Don’t wait until you’re under attack to “discover” Facebook and Twitter.

- Evaluate the threat. Where and how did it start? Who’s the source? How influential is the source? (But remember, as with the bus tweet, influence can be earned online in seconds.)

- Don’t let mistakes or factual misstatements about you or your organization persist online.

- When it’s time to respond, do so as quickly as possible. An honest, factual, sincere response is more important than a perfectly polished response. Get in the game.

- Most of all, be transparent, tell the truth and back up your words with actions.

Thom Fladung worked at newspapers for 33 years and hated it whenever a newspaper ran a fake story as part of an April Fools prank. For more on how to effectively communicate amid a crisis or reputation-challenging event, contact Hennes Communications and ask about our social media training sessions.