Apologies, Non-Apologies, Fauxpologies, Conditional Apologies & Past Exoneratives

By Stan Carey:

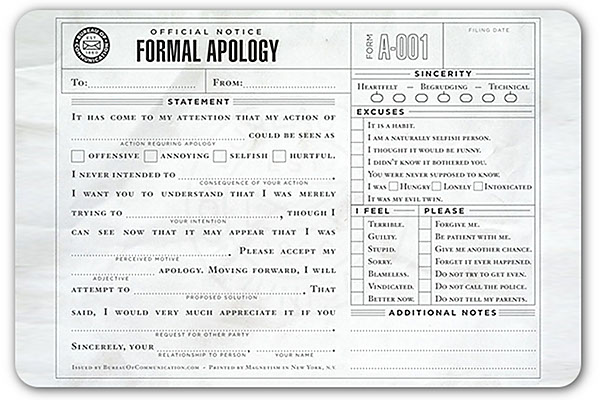

Writing in 2012 about the nature of apologies, I said that being sorry is about more than just saying the words, “but the words, as an explicit admission of wrongdoing or shortcoming, can be an important part of reconciliation.” With a non-apology the aims and effects are wholly different. The person delivering it can move on, professing the matter dealt with—a routine step in self-mythologizing narratives—but recipients of the unapology feel continued frustration, even disgust, at the failure to accept responsibility.

When guilty people aren’t really sorry (or are worried about the legal implications), they don’t want to make a direct, unqualified admission. This is not a definitive science: Someone might say “I’m very sorry for what I did” and not mean it, or apologize tortuously but with heartfelt intent. Nevertheless, non-apologies tend to ring conspicuously false, being variously couched in ifs, buts, hedges, deflection, qualification, self-absorption, euphemism, defensiveness, obfuscation, and the agentless passive voice (“Mistakes were made”). I’m just sorry I got called out is a common subtext.

For the rest, click here.